Why oh why am I still having to write lengthy corrections to articles about the history of India Pale Ale? Well, apparently because the Smithsonian magazine, the official journal published by the Smithsonian Institution, is happy to print articles about the history of India Pale Ale without anybody doing any kind of fact-checking – and William Bostwick, beer critic for the Wall Street Journal, appears to be one of those writers who misinterpret, make stuff up and actively get their facts wrong.

The article Bostwick had published on Smithsonian.com earlier this week, “How the India Pale Ale Got Its Name”, is one of the worst I have ever read on the subject, crammed with at least 25 errors of fact and interpretation. It’s an excellent early contender for the Papazian Cup. I suppose I need to give you a link, so here it is, and below the nice picture of the Bow Brewery are my corrections.

“The British Indian army” – most of the British troops in India in the 18th century were in the three private armies run by the East India Company. There was no such thing as “the British Indian army” at that time.

“Soaking through their khakis in the equatorial heat” – khaki uniforms were not used by the British until the 1880s. Calcutta is almost 1,500 miles from the equator.

“The first Brits to come south were stuck with lukewarm beer—specifically dark, heavy, porter, the most popular brew of the day in chilly Londontown, but unfit for the tropics.”

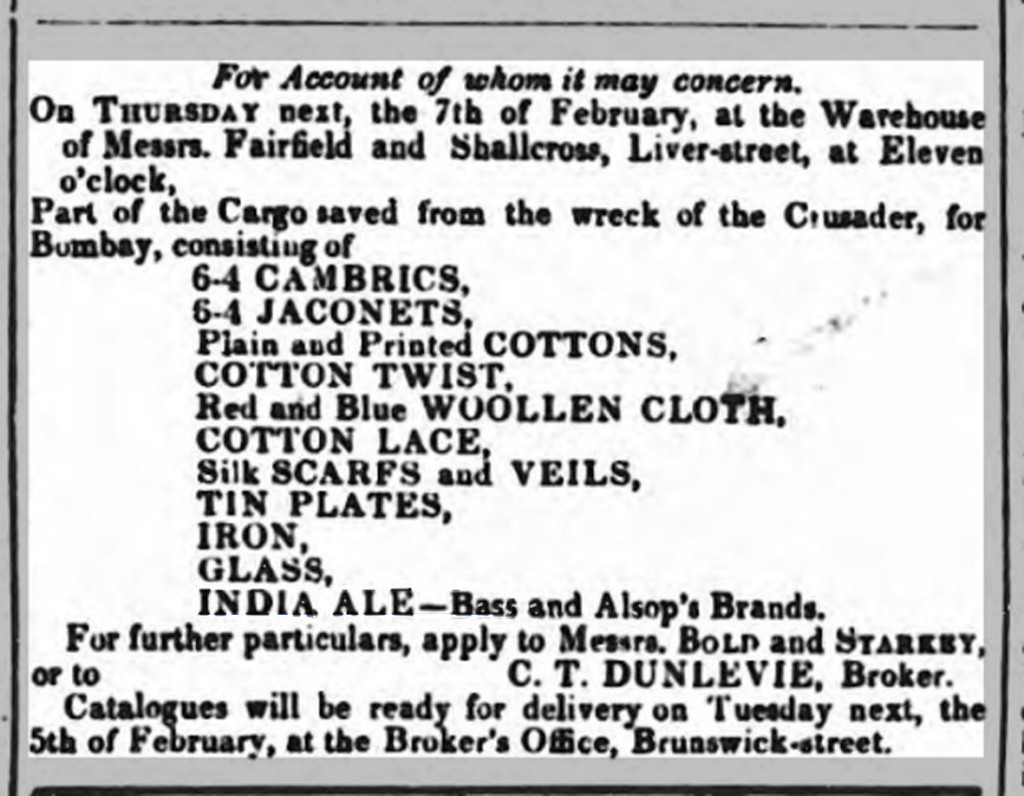

Ignoring the fact that to get to India from Britain you travel east, porter continued to be exported to India from Britain for more than a century from at least the 1780s, with the East India Company in the 1850s ordering large quantities of porter from London brewers. The troops drank porter, and enjoyed it. Dark beers can be very refreshing in hot weather, and stouts are still made in hot climates, from the West Indies to Indonesia.

“One Bombay-bound supply ship was saved from wrecking in the shallows when its crew lightened it by dumping some of its cargo — no great loss, a newspaper reported, ‘as the goods consisted principally of some heavy lumbersome casks of Government porter.'”

The ship was trying to get away from Bombay, not into it, and this is a quote from 1851, just to underline the point about how long porter was exported to India.

“Most of that porter came from George Hodgson’s Bow brewery, just a few miles up the river Lea from the East India Company’s headquarters in east London.”

While Hodgson exported porter to India, there is no evidence that he was supplying “most” of it. The East India Company’s headquarters weren’t in east London, but in Leadenhall Street in the City. What was in “east London”, or more accurately, at Blackwall, on the Thames three miles to the east of the City, were the moorings used by the East Indiamen. They weren’t “a few miles” from Hodgson’s Bow brewery, but 1.3 miles as the crow flies and 2.5 miles if you follow the meandering Lea.

“Outward bound, ships carried supplies for the army, who paid well enough for a taste of home, and particularly for beer”

The articles carried on board the East Indiamen from London to India were for sale mostly to the European civilians living there, including the “civil servants” of the East India Company, not for “the army”. Beer was only a small part of what was carried, which included wine, brandy, Madeira and cider, plus all kinds of foodstuffs and many other items, from china to furniture to leather goods to clothes, unobtainable in India.

“Its clippers rode low in the water, holds weighed with skeins of Chinese silk and sacks of cloves.”

A clipper and an East Indiaman are two entirely different sorts of sailing ship, one built for speed, the other for carrying cargo and passengers. If you call an East Indiaman a clipper, you just make yourself look stupid. And the majority of the goods on board an East Indiaman was likely to be tea and cotton.

“The trip to India took at least six months” – no, it took between four and six months

“Hodgson sold his beer on 18-month credit, which meant the EIC could wait to pay for it until their ships returned from India, emptied their holds, and refilled the company’s purses.”

But it wasn’t the East India Company buying the beer from Hodgson, it was being bought by the East Indiamen captains and commanders to sell on their own accounts.

“Still, the army, and thus the EIC, was frustrated with the quality Hodgson was providing. Hodgson tried unfermented beer, adding yeast once it arrived safely in port. They tried beer concentrate, diluting it on shore. Nothing worked. Nothing, that is, until Hodgson offered, instead of porter, a few casks of a strong, pale beer called barleywine or ‘October beer.’”

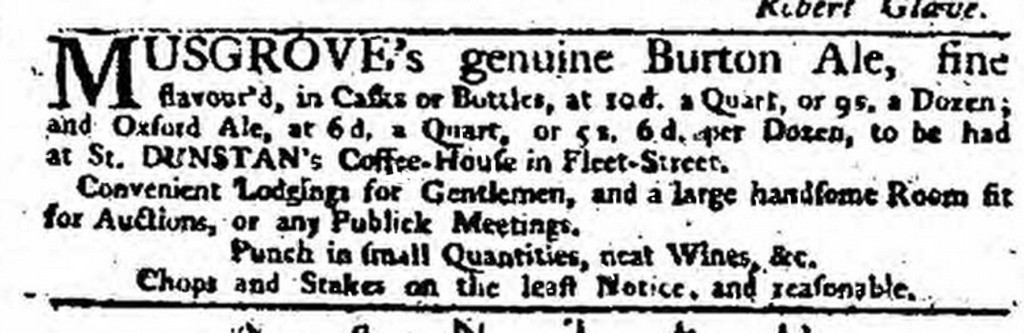

This is complete rubbish. There is no evidence for any of this, no sending unfermented beer out – that would never have worked, as anyone who claims to know about beer would surely realise – and no concentrating it and then diluting it. There is no indication that “the army” (not an institution that existed anyway) or the East India Company cared at all about Hodgson’s beer. “Barleywine” is an anachronism: the term isn’t used by British brewers until the late 19th century, and even then as two words, not one, which is an Americanism. In any case, Hodgson was exporting both pale ale and porter to India from at least 1790, and pale ale – brewer unknown – was being exported to India from at least 1784.

“It got its name from its harvest-time brewing, made for wealthy country estates “to answer the like purpose of wine” — an unreliable luxury during years spent bickering with France. … these beers were brewed especially rich and aged for years to mellow out. Some lords brewed a batch to honor a first son’s birth, and tapped it when the child turned eighteen. To keep them tasting fresh, they were loaded with just-picked hops. Barclay Perkins’s KKKK ale used up to 10 pounds per barrel. Hodgson figured a beer that sturdy could withstand the passage to India.”

October beer was brewed months after the harvest, and was not, in any case, the same beer that country gentlemen drank in place of brandy – not French wine – nor the same beer that the landed gentry laid down until their sons became 21 – not 18. They weren’t “loaded with just-picked hops” to keep tasting fresh – that’s something the writer has made up – and Hodgson didn’t work out on his own that well-hopped beer would survive the journey East, that was known since at least the 1760s.

“He was right. His first shipment arrived to fanfare. On a balmy January day in 1822, the Calcutta Gazette announced the unloading of ‘Hodgson’s warranted prime picked ale of the genuine October brewing. Fully equal, if not superior, to any ever before received in the settlement.'”

This is nonsense. The 1822 shipment was just the latest in more than 30 years of shipments of pale ale by Hodgson to India.

“Hodgson’s sons Mark and Fredrick, who took over the brewery from their father soon after”

Mark Hodgson was running the brewery by 1811. It was Frederick Hodgson, not Fredrick.

“They tightened their credit limits and hiked up their prices, eventually dumping the EIC altogether and shipping beer to India themselves.”

I repeat: it wasn’t the East India Company shipping the beer to India, but the EIC captains and commanders, acting as private individuals.

“By the late 1820s, EIC director Campbell Marjoribanks, in particular, had had enough. He stormed into Bow’s rival Allsopp with a bottle of Hodgson’s October beer and asked for a replica. Allsopp was good at making porter — dark, sweet, and strong, the way the Russians liked it”

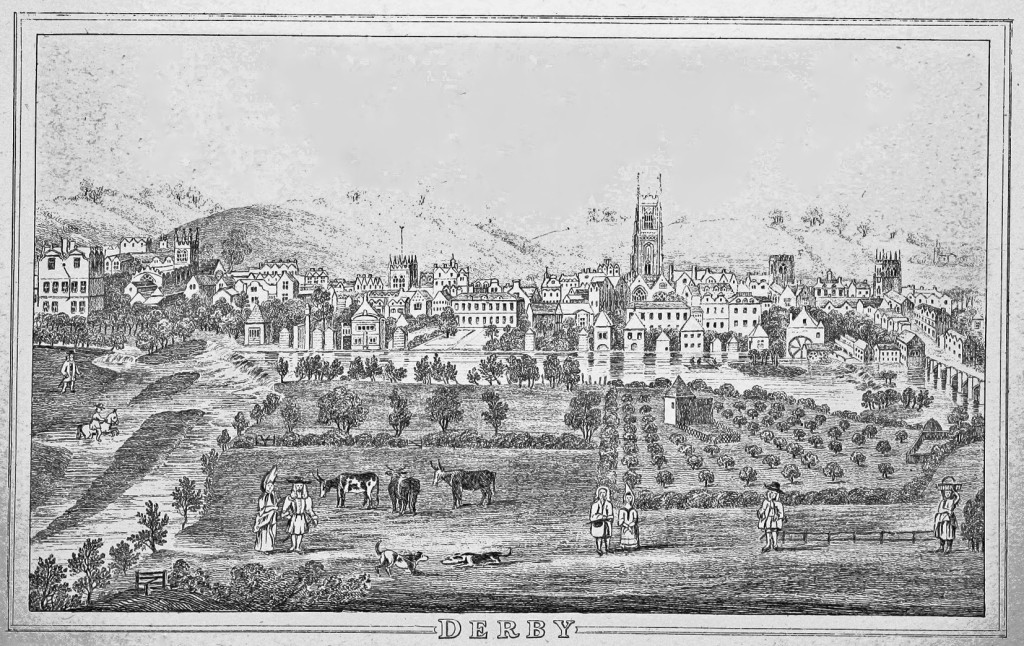

It was 1822, not “the late 1820s”, that Marjoribanks spoke to Allsopp, at Marjoribanks’s home in London, not at Allsopp’s brewery in Burton upon Trent. Allsopp was not a porter brewer, but a brewer of Burton ale, a totally different beer. Porter wasn’t necessarily sweet.

“When Sam Allsopp, only a few years shy of turning the business over to his sons, tried the sample of Hodgson’s beer Marjoribanks had brought, he spit it out — too bitter for the old man’s palate.”

Samuel Allsopp was 42 in 1822, so certainly not an old man. He would run the company for another 16 years. There is no evidence he spat Hodgson’s beer out.

“He asked his maltster, Job Goodhead, to find the lightest, finest, freshest barley he could. Goodhead kilned it extra lightly, to preserve its subtle sweetness – he called it ‘white malt’”

The author is making that all up again. There is no evidence Allsopp asked Goodhead to find “the lightest, finest, freshest barley he could”, nor that Goodhead called the pale ale malt he made “white malt”. “White malt” and pale ale malt are different types.

“To recreate Allsop’s legendary brew, I’d need the best ingredients available today, and that meant Maris Otter malt and Cascade hops.”

It’s “Allsopp”. And to recreate it you would need an authentically 18th/19th century hop such as East Kent Goldings, not Cascade, which is the kind of American hop British brewers dismissed in the 19th century for their supposedly unpleasant flavours.

That article looks to have been based on a chapter in a book Bostwick had published last year, called The Brewer’s Tale: A History of the World According to Beer. I hadn’t come across this before, thankfully, and I have absolutely no intention of buying it, but I took a peek at what is available via Amazon’s “Look Inside” function, and it appears to be as crammed with errors as the article on IPA is. You can only see the first 60 or so pages via Amazon, but here are some of the errors I found even in that short section:

“Dark-age tribes had spice cabinets full of henbane, ergot and other bog-grown oddities”

Henbane doesn’t grow in bogs, unless you’re making a bad British English pun (Nicholas Culpepper said in 1653 that “whole cart loads of it may be found near the places where they empty the common Jakes”). It grows on chalky and sandy soils. Ergot is a fungus that infects rye (mostly) and wheat and barley (sometimes), Again, it’s not something that grows in a bog. Nor is it something that is known to have ever been deliberately used by humans to induce hallucinations, unlike henbane.

“Brewers eventually learned through trial and error to reproduce those warm, oxygen-rich environments Saccharomyces likes best” – ah, really? My understanding is that while you need oxygen at the start of fermentation, to encourage yeast growth, you soon want more anaerobic conditions, or the yeast won’t make alcohol.

“Caked in a Neanderthal molar discovered deep in a Belgian cave, a single charred kernel of barley, last munched some thirty thousand years ago, is our earliest record of that agricultural revolution”

This is a wildly exaggerated and highly inaccurate version of the findings of Amanda Henry, Alison Brooks and Dolores Piperno, reported in 2010, from their analysis of the dental calculus found on the teeth of Neanderthal skeletons found in the Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan, and Spy Cave (pronounced “spee”), Belgium. It certainly wasn’t “a single charred kernel of barley” that was found, but dozens of tiny grains of starch. Some of those grains of starch were identified as coming from barley, and some of those from cooked barley – but only on the Neanderthal teeth from Iraq. It would be absolutely staggering if evidence pointing to barley consumption dating back 36,000 years was found in the area of modern Belgium, since this would be 30,000 years before barley and other grains are reckoned to have reached northern Europe, brought by farmers from their original home in the Middle East. Anybody studying the history of beer really ought to know that talking about barley in Northern Europe that far back is nonsense. Shanidar Cave is in the Zagros Mountains, on the edge of the area where, long after the Neanderthals disappeared, settled agriculture developed, using just those varieties of grain, like barley, that the Shanidar Neanderthals were evidently gathering wild – and cooking – 40,000 years ago. So there is a fascinating link between the Neanderthals and modern agriculture – but it ain’t the one Bostwick claims it is.

“the Greek wit and poet Athenaeus contrasted his own civilized ways with savage tribes who drink, he wrote, “a beer made of wheat prepared with honey, and oftener still without honey.”

Athenaeus was quoting another writer, Posidonius, in that passage, talking about the Celts of Gaul, and neither writer called them “savage tribes”. Posidonius was actually contrasting what the wealthy Celts drank – wine – with what “those who are poorer” drank. Bostwick uses the translation of the passage by CD Yonge from 1854: I prefer that of Max Nelson: “Among those who are poorer there is wheaten beer prepared with honey, and among the majority there is plain [beer]. It is called korma.”

“Germanic tribes were cultivating wheat and barley by 5000BC and Celtic bands on the British Isles soon after”

It is total nonsense to talk about “Germanic” and “Celtic” tribes 7,000 years ago. We’re barely in the time of the Proto-Indo-Europeans that far back. Germanic tribes cannot be identified until around 1500BC, while the origins of the Celts are normally pitched around the same time or slightly later.

“Stranded on the windswept Scottish border in fortresses at Bearsden and Vindolanda, Augustan legions …”

Ignoring the anachronism of taking about the “Scottish” border at the time of the Romans, Bearsden is in Glasgow, 80 miles north of the modern Scottish border, while Vindolanda is 26 miles south of the border. The legions weren’t “Augustan” – Augustus died 70 years before Roman troops were stationed at Vindolanda.

“The first brewer in British history we know by name, in fact, was a Roman: Arrectus”

The name was Atrectus. We don’t know what nationality he was, but Atrectus is reckoned to be a Gallic or Gallo-Belgic name, so the Vindolanda brewer was unlikely to be Roman.

“Some beer writers are sticklers about the difference between beer and ale, saying beer refers to a drink made with hops and ale to one without. I find that distinction arbitrary and etymologically suspect and will ignore it”

I don’t know any beer writer who says ale can only refer to a drink made without hops. I DO know beer writers who point out that when you’re talking about historical malt liquors, it’s important to distinguish between beers and ales in the context of their times, when the two words meant different things at different periods. That’s not an “arbitrary” distinction, but an important historical one, and etymology has nothing to do with it.