![Jacques Cartier]()

Jacques Cartier supposedly pictured learning from a Canadian First Nationer how to save his men from scurvey: but the chap with the buckskin suit and the metal axe with the tepees in the background looks like a Plains Indian 1,500 miles and 220 years away from home rather than a Huron

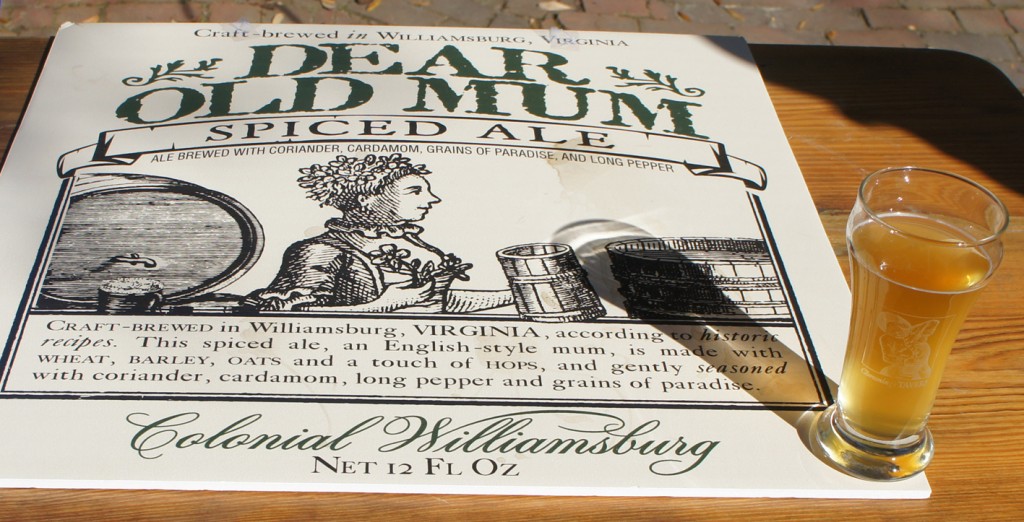

Early European explorers in North America had to be shown the healthy properties of the spruce tree by the existing inhabitants. When the Breton explorer Jacques Cartier overwintered in Quebec in 1535-36 on his second visit to the land he had named Canada, almost all his men fell ill with scurvy through lack of fresh food, leaving just ten out of 110 well enough to look after the rest. Huron Indian women showed them how to make tea and poultices from the bark of a local tree, which quickly returned them to health. That tree was probably White Cedar, Thuja occidentalis, a member of the cypress family, rather than spruce. But later French settlers turned to spruce trees, a better source of Vitamin C, and thus a better way to combat scurvy, the curse of long-distance voyagers, than cedars. The secretary to the new French governor of Cape Breton Island, Thomas Pichon, writing in 1752, noted that the inhabitants of Port-Toulouse (now St Peter’s) “were the first that brewed an excellent sort of antiscorbutic [“la bière très bonne” in the original French], of the tops of the spruce-fir”, “Perusse” or “Pruche” in Pichon’s French.

Around the same time, the Swedish-Finnish botanist Pehr Kalm, who travelled in North America from 1748 to 1751, apparently found the French in Canada drank little else but spruce beer. In his letters to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, he wrote:

“Among other liquors commonly drank in the European plantations in the North of America there is a beer which deserves particular notice; it is brewed from a kind of pine that grows in those parts and is by botanists called Abies Piccea foliis brevibus conis minimus [black spruce, Picea mariana]. The French in Canada call it Epinette and Epinette Blanche, the English and Dutch call it Spruce.” Spruce beer, Kalm said, “is chiefly used by the French in Canada; a considerable quantity is indeed made by the Dutch who live round Hudson’s river, in the most Northern parts, but the English seldom have it except in New England and New Scotland; because in Canada the tree is very common, but at Albany it is so scarce that the people are obliged to go some miles for it; and in the other English plantations it is hardly to be met with.”

Kalm gave much detail about the making of spruce beer, telling the Academicians:

“I had no opportunity to see the method of making this liquor used by the Dutch, but often drank it amongst them, and thought it very good. The account they gave me of preparing it is as follows: take 12 gallons of water and set it to boil in a copper; put into it about a pint and half or as much as can be held between two hands, of cuttings of the leaves and branches of the pine; let it boil about an hour, and pour it into a vessel, and leave it to cool a little; then put the yeast into the vessel to make the wort ferment; in to take away the resinous taste, put a pound of sugar amongst it. After it has done working, it may be put into hogsheads or barrels, but it is reckoned best to bottle it directly. It will keep a great while, and will not grow so soon sour in the summer as malt liquor. It looks clear and like common beer, has an agreeable taste, and when pour’d out of a bottle into a glass mantles like ale. It is reckoned very wholesom, and has a diuretick quality.

“When I afterwards came to Canada, I had several times an opportunity to see the French prepare this beer, which, as they use no malt liquor, is their only drink, except wine brought from France, which is pretty dear. Their way of brewing it is this: After having put the cuttings of the pine into the water, they lay some of the cones of the tree amongst it, for the gum which is contained in them is thought very wholesom; and makes the beer better. The French do not cut the branches and leaves of the pine nearly so fine as the Dutch; for if the branches are small enough to go into the copper, they do no more to them, and they measure the quantity no otherwise than by putting them into the till they come even with the surface of the water. While it is boiling they take some wheat, put it into a pan over the fire and roast it as we do coffee, till it is almost black; all the while stirring, shaking and turning it about in the pan, when that is done they throw it into the copper with some burnt bread.

“Rye is as fit for this purpose as wheat, barley is better than either, and Indian corn is better than barley. The reasons given me for putting this burnt corn and bread into the water are: 1st, and chiefly, to give it a brownish colour like malt liquor; 2nd, to make it more palatable; 3rd, to make it some more nourishing. When it has continued boiling till half the quantity only of the water remains in the copper, the pine is taken out and thrown away, and the liquor is poured into a vessel thro’ a sieve of hair cloth, to prevent the burnt bread and corn from mixing with it. Then some sirrup is put into the wort to make it palatable, and to take away the taste which the gum of the tree might leave behind. The wort is then left to cool after some yeast has been put to it, and nothing remains to be done before it is tunned up but skimming off what, during the fermentation, has risen up on the surface; and in four and twenty hours it is fit to be drank. As there is a great resemblance between the pine and that which is common in Sweden, it would be worth while to try whether ours could be made use of in the same manner.”

![Black spruce]()

Black spruce, Picea Mariana

Kalm’s description of spruce beer brewing involved very little extra fermentable material, suggesting the French and Dutch found enough fermentable material in the spruce sap itself. However, John Claudius Loudon, writing in 1838, repeated an account of spruce beer brewing by the 18th century French physician, naval engineer and botanist Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau (1700-1782), apparently from the Traité des arbres fruitiers of 1768, clearly matching French Canadian practice, but with plenty of molasses or sugar:

“To make a cask of spruce beer, a boiler is necessary, which will contain one fourth part more than the quantity of liquor which is to be put into it. It is then filled three parts full of water, and the fire lighted. As soon as the water begins to get hot, a quantity of spruce twigs is put into it, broken into pieces, but tied together into a faggot or bundle, and large enough to measure about 2 ft. in circumference at the ligature. The water is kept boiling, till the bark separates from the twigs. While this is doing, a bushel of oats must be roasted, a few at a time, on a large iron stove or hot plate ; and about fifteen galettes [flat yeasty cakes], or as many sea biscuits, or if neither of these are to be had, fifteen pounds of bread cut into slices and toasted. As these articles are prepared, they are put into the boiler, where they remain till the spruce fir twigs are well boiled. The spruce branches are then taken out, and the fire extinguished. The oats and the bread fall to the bottom, and the leaves, &c., rise to the top, where they are skimmed off with the scum. Six pints of molasses, or 12 lb. or 15lb. of coarse brown sugar, are then added ; and: the liquor is immediately tunned off into a cask which has contained red wine; or, if it is wished that the spruce beer should have a fine red colour, five or six pints of wine may be left in the cask. Before the liquor becomes cold, half a pint of yeast is mixed with it, and well stirred, to incorporate it thoroughly with the liquor. The barrel is then filled up to the bung-hole, which is left open to allow it to ferment ; a portion of the liquor being kept back to supply what may be thrown off by the fermentation. If the cask is stopped before the liquor has fermented 24 hours, the spruce beer becomes sharp, like cider ; but, if it is suffered to ferment properly, and filled up twice a day, it becomes mild, and agreeable to the palate. It is esteemed very wholesome, and is exceedingly refreshing, especially during summer.”

Loudon also quoted “Michaux”, either the French naturalist Andre Michaux or his son Francois, as saying: “the twigs are boiled in water, a certain quantity of molasses or maple sugar is added, and the mixture is left to ferment,” and also: “The essence of spruce (which is what spruce beer is made from in this country) is obtained ‘by evaporating to the consistence of an extract the water in which the ends of the young branches of black spruce have been boiled.’ Michaux adds that he cannot give the details of the process for making the extract, as he has never seen it performed; but that he has often observed the process of making the beer, in the country about Halifax and the Maine, and that he can affirm with confidence that the white spruce is never used for that purpose.”

The British Army in North America looks to have learnt from the French the importance of spruce beer for treating and preventing scurvy: there is a strong argument for saying that spruce beer helped the British defeat the French and conquer Canada, by keeping troops healthy who would otherwise have fallen ill with scurvy. John Knox, born in Sligo, who served as an officer in North America between 1757 and 1760 with the 43rd Regiment of Foot, said the troops from New England temporarily occupying Louisbourg after its capture in 1745 were supplied with spruce beer, “this liquor being thought necessary for the preservation of the healths of our men, as they were confined to salt provisions, and it is an excellent antiscorbutic: it is made from the tops and branches of the Spruce-tree, boiled for three hours, then strained into casks, with a certain quantity of molasses, and, as soon as cold, it is fit for use.” When British troops were again involved in a campaign against the French in Nova Scotia in 1757, their commander, the Earl of Loudoun, had insisted on an allowance of two quarts of spruce beer per man each day, for which the troops paid seven pence in New York currency, equal to four and one-twelfth pence sterling, later increased to five pints a day.

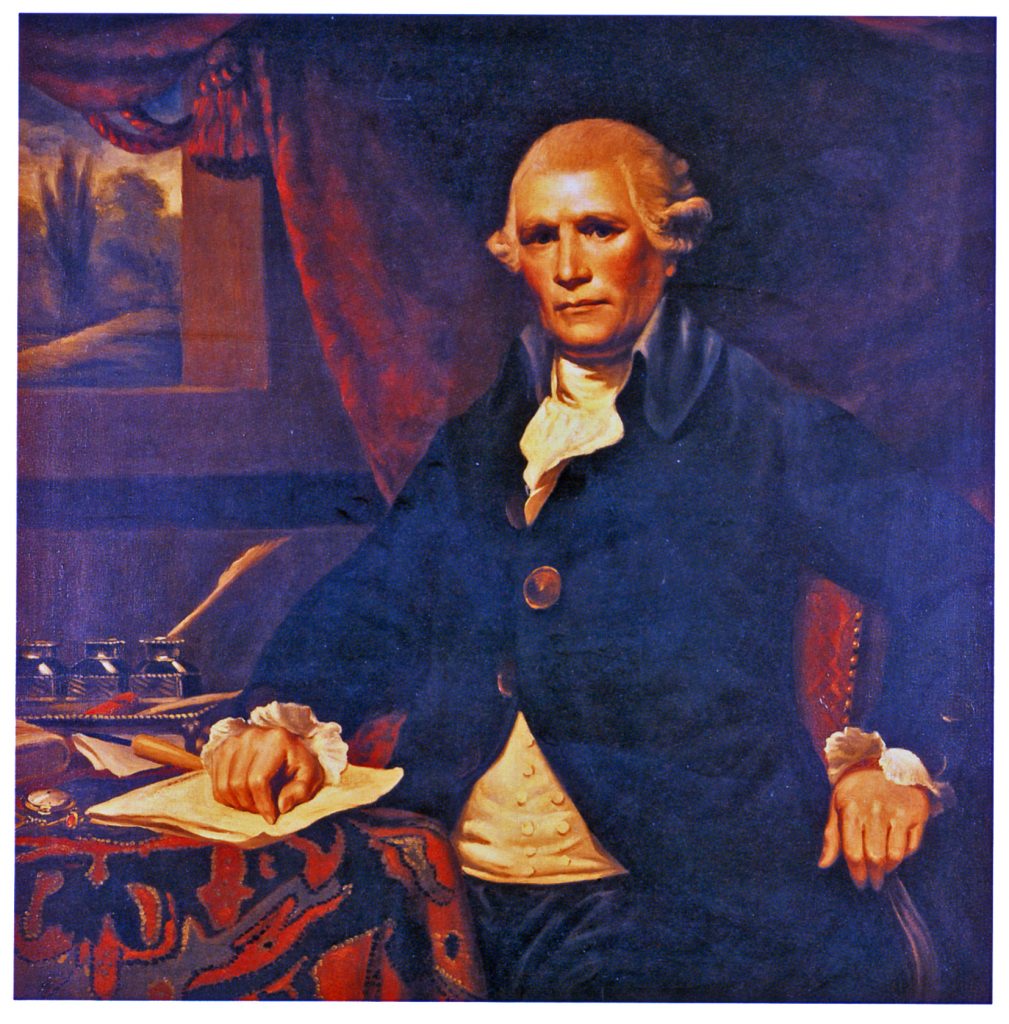

![2008_EX02_01 007]()

General Jeffrey Amherst

General Jeffrey Amherst, who followed the Earl of Loudon as commander in chief of British forces in North America, was equally insistent that the troops be well supplied with spruce beer, “for the health and convenience of the troops”, and a “Breweree” (sic) was set up when the British Army was camped at the head of Lake George in what is now north-east New York State in June 1759 with each regiment donating one man to help with the brewing, and instructions to allow five quarts of molasses to every barrel of spruce beer. When Amherst’s troops moved north to capture the French Fort Carillon, subsequently renamed Fort Ticonderoga, the next month, each regiment took with it eight barrels of spruce beer, with a barrel to each company of Grenadiers and “Light Infentry”. Amherst considered spruce beer important enough to record a recipe for it in his journal on 15 August 1759, involving boiling “7 pounds of good Spruce” until the bark peels off and adding three gallons of molasses to the spruce-water, to make 30 gallons of beer.

Later on at Ticonderoga, in 1776, after the fort had been captured by American forces from the British during the War of Independence, two enterprising sergeants in the 5th Continental Regiment from New Hampshire, William Chamberlin and Seth Spring, crossed Lake Champlain to gather boughs of spruce, brought them back and with two quarts of molasses and a “quantity” of “spicknard or Indian root” (American spikenard, Aralia racemosa, a member of the ginseng family) for added flavour, brewed a barrel of beer. It was instantly popular with the other troops, and Spring was sent to Fort George to bring back two barrels of molasses to make more beer to sell. After six or seven weeks, Chamberlin recorded, he and Spring had made three hundred dollars between them.

An edition of the physician Richard Brookes’s General Practice of Physic in 1765 said:

“Poor People that winter in Greenland under vast Disadvantages in point of Air and Diet, preserve themselves from the Scurvy by Spruce Beer, which is their common Drink. Likewise the simple Decoction of Fir Tops has done Wonders. The Shrub Black Spruce of America makes this most wholesome Drink just mentioned and affords a Balsam superior to most Turpentines. It is of the Fir Kind. A simple Decoction of the Tops, Cones, Leaves, or even of the green Bark or Wood of these, is an excellent Antiscorbutic; but perhaps it is much more so when fermented, as in making Spruce Beer. This is done by Molosses, which by its diaphoretic Quality, makes it a more suitable Medicine. By carrying a few Bags of Spruce to Sea, this wholesome Drink may be made at any Time. But when Spruce cannot be had, the common Fir-Tops used for Fuel in the Ship should be first boiled in Water, and then the Decoction should be fermented with Molosses; to which may be added a small Quantity of Wormwood and Root of Horseradish. The fresher it is drank the better.”

Four years later 1769 a book called The London Practice of Physic, listing treatments for scurvy, gave a recipe for spruce beer as follows:

Take twelve gallons of water and put therein three pounds and a half of black spruce, and boil it for three hours; then put to the liquor seven pounds of molasses just boil it up, strain it through a sieve when milk-warm, put to it about four spoonfulls of yeast to work it; it soon becomes fit for bottling, perhaps in five or six days.

Later versions of this recipe said it was called “chowder beer” and claimed it originated in Devon, adding that “two gallons of melasses [sic] are sufficient for a hogshead of liquor, but if melasses cannot be procured treacle or coarse sugar will answer the purpose.”

Captain James Cook experimented with spruce beer on his second voyage to the Pacific, from 1772 to 1775, making a batch when he arrived in New Zealand. Cook wrote:

“We at first made it of a decoction of spruce leaves [the spruce Cook used was the New Zealand rimu, Dacrydium cupressinum]; but finding that this alone made the beer too astringent, we afterwards mixed with it an equal quantity of the tea-plant, (a name it obtained in my former voyage from our using it as tea then as we also did now) which made the beer extremely palatable, and esteemed by every one on board [this was the mānuka, Leptospermum scoparium, found in New Zealand and south-east Australia]; we brewed it in the same manner as spruce beer, and the process is as follows: First, make a strong decoction of the small branches of the spruce and tea-plant, by boiling them three or four hours, or until the bark will strip with ease from off the branches; then take them out of the copper, and put in the proper quantity of molasses, ten gallons of which are sufficient to make a tun, or two hundred and forty gallons of beer; let this mixture just boil; then put it into the casks, and to it add an equal quantity of cold water, more or less, according to the strength of the decoction or the taste: when the whole is milk-warm, put in a little grounds of beer or yeast, if you have it, or any thing else that will cause fermentation, and in a few days the beer will be fit to drink. After the casks have been brewed in two or three times, beer will generally ferment itself, especially if the weather is warm. As I had inspissated juice of wort [a concentrated form or wort the Admiralty was experimenting with in the hope that it could be used to make beer on long voyages on board], and could not apply it to a better purpose, we used it together with molasses or sugar to make these two articles go farther.”

Cook and his men brewed spruce beer in New Zealand again in February 1777 on his third and last voyage to the Pacific, and also in April 1778, at Nootka Sound on the Canadian west coast, where enough beer was brewed “to last the ship’s company for two or three months”. When Cook’s two ships reached Unalaska Island in the Aleutians early in October 1778, Cook recorded that both crews were free of scurvy, putting this down in part to the spruce beer, which was drunk every other day.

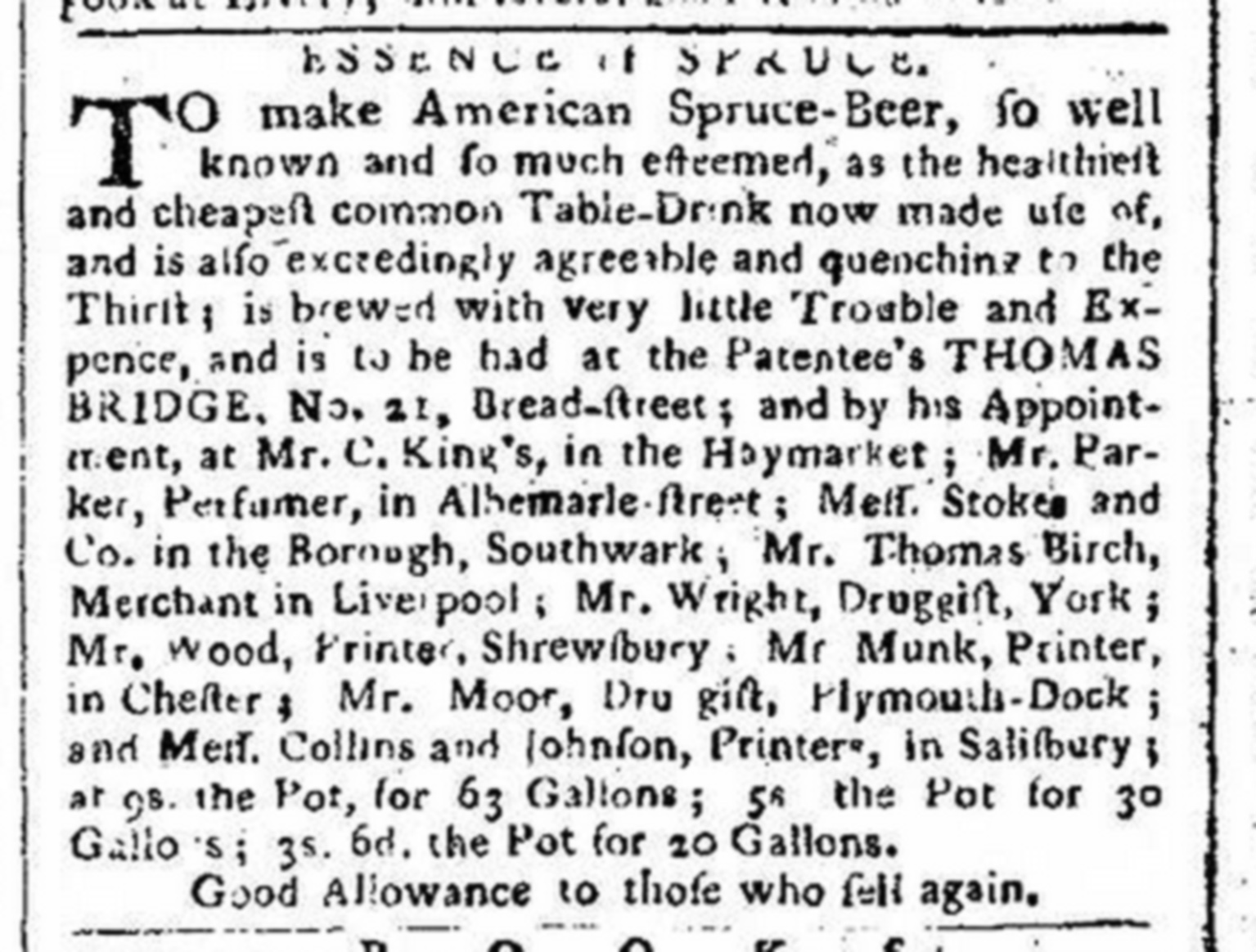

![Essence of Spruce ad 1777]() Spruce beer, (not strictly, of course, a “beer”, since it was not made from malted grain) was meanwhile taking off in Britain thanks to the invention of in Canada of “essence of spruce”. Essence of spruce was advertised in Lloyd’s Evening Post in London in February 1770, but only as a cure for “Scorbutic Complaints”, with no mention of brewing with it. The following year, Dr Henry Taylor, of Quebec, patented “a method of producing an essence or extract of spruce so perfect that one pound and a quarter will make sixty gallons of fine spruce beer which will be fit to drink in three days in any climate.” Taylor’s method was to place “tops or small branches” of spruce in a still, distil off half the liquor, with “all the essential oil on the top of the glass … to be carefully saved”, then run the “residuum” in the still into a boiler where there were more “fresh tops or branches of spruce” and boil that up to reduce it. The residuum was then to be boiled again with fresh spruce tops or branches, and then the “essential oil” mixed in.

Spruce beer, (not strictly, of course, a “beer”, since it was not made from malted grain) was meanwhile taking off in Britain thanks to the invention of in Canada of “essence of spruce”. Essence of spruce was advertised in Lloyd’s Evening Post in London in February 1770, but only as a cure for “Scorbutic Complaints”, with no mention of brewing with it. The following year, Dr Henry Taylor, of Quebec, patented “a method of producing an essence or extract of spruce so perfect that one pound and a quarter will make sixty gallons of fine spruce beer which will be fit to drink in three days in any climate.” Taylor’s method was to place “tops or small branches” of spruce in a still, distil off half the liquor, with “all the essential oil on the top of the glass … to be carefully saved”, then run the “residuum” in the still into a boiler where there were more “fresh tops or branches of spruce” and boil that up to reduce it. The residuum was then to be boiled again with fresh spruce tops or branches, and then the “essential oil” mixed in.

The Royal Navy quickly picked up on Taylor’s invention. A letter that year, 1771, from the Admiralty to the Treasury refers to “essence of Spruce” from Quebec, “which when brewed into beer may be of great service to the navy in preserving the seamen from scurvy.” Vice-Admiral Samuel Graves, who was in command of the North America Station at the start of the American War of Independence, wrote in a letter to the Secretary of the Admiralty Board from Boston, Massachusetts in September 1775 that “The Seamen always continue healthy and active when drinking spruce Beer”, and in the log of the 70-gun HMS Boyne, one of the ships under Graves’s command, are many entries of butts of spruce beer taken on while it was lying in Boston harbour in 1774-1775. (Spruce beer was still being brewed for Royal Navy ships in 1807.)

Taylor had a partner in patenting the essence, Thomas Bridge, of Bread Street, London, and by April 1774 Bridge was boasting in print that he had the rights to “the sole making and vending the said Essence.” Bridge told prospective customers that one hogshead of essence would make five hundred hogsheads of beer, and a pound and a quarter of it would make 63 gallons of beer that “may be brewed with very little trouble at sea or land, without fire … and will be fit for use in three or four days. It was, he said, “a excellent table beer, is the best anti-scorbutic yet discovered, is also a fine substitute for malt liquor to people afflicted with the stone, gravel and many other disorders,, as it is allowed to be a great purifier of the blood, by dissolving all viscid juices, opening ostructions [sic] of the viscera and the more distant glands.” By 1784 Bridge was not just supplying the essence, but also brewing “the best double American spruce beer” himself at his premises in Bread Street, “under the inspection of a gentleman long used to that business in America”, and selling it in both bottles and casks.

He had a rival, J Ellison, of St Alban’s Street, Pall Mall, and Red Lion Street, Whitechapel, who ran a lengthy advertisement on the front of the Morning Herald and Daily Advertiser in September 1783 proclaiming that the virtues of spruce beer could be credited to the large amount of “fixable air” – carbon dioxide – it contained, and claiming that experiments carried out under the instructions of “Dr Higgins” – Bryan Higgins, a scientist who ran a “school of practical chemistry” in Soho, London in the 1770s – showed a gallon of spruce beer would release nearly two gallons of “fixable air” when the cork was removed from the bottle, “which … cause the intumescence and frothing which always appear when a bottle of good of Spruce Beer is quickly uncorked.” Summoning the names of several more contemporary scientists, including Joseph Priestley and Dr Joseph Black, Ellison said they all agreed that “fixable air” was “a powerful and a necessary part of the fluids and solids in sound bodies”, and to fixable air was ascribed “the most salutary effects in diverse diseases.” Since spruce beer “contains so great a quantity of this active spirit,” Ellison said, “it may fairly be inferred that the Spruce Beer is most salutary which is made to retain the greatest quantity of fixable air,” something he was “particularly attentive to.”

!['What say we get it on, kid? After all, we both like spruce beer.' '"I'm vewry sorry, M Knightley, I could never grant my lifelong affections to a man who wore hats like that.']()

‘What say we get it on, kid? After all, we both like spruce beer.’ ‘I am so very sorry, Mr Knightley, truly, and I am most flattered by your expressions of regard, which I cannot but be sensible are most undeserved, but I could never bring myself to give my heart and hand for life to a man who wore a hat like that.’

Jane Austen liked spruce beer, agreeing with the anonymous author of The Family Receipt-Book or Universal Repository of Domestic Economy, published 1808, that “The salubrity of spruce beer is universally acknowledged.” Indeed, she liked it enough to make it herself, at home, more than once. In a letter dated December that same year to her sister Cassandra from Castle Square in Southampton, where Jane was living in the home of her brother Frank, then a captain in the Royal Navy, she wrote: “we are brewing Spruce Beer again”, with an oblique joking reference to the great porter casks of Henry Thrale, the former owner of the Anchor brewery in Southwark. In Emma, written in 1815, both Emma Woodhouse and her lifetime friend, the landowner George Knightley, admit to a liking for spruce beer, and Mr Knightley gives the local vicar, Mr Elton, who has “resolved to learn to like it too” (probably to try to ingratiate himself with Emma), tips on brewing it. It is more than likely that Jane Austen had been introduced to spruce beer by her brother, who had joined the Royal Navy in 1786, and had a reputation as a commander concerned with the welfare of his men.

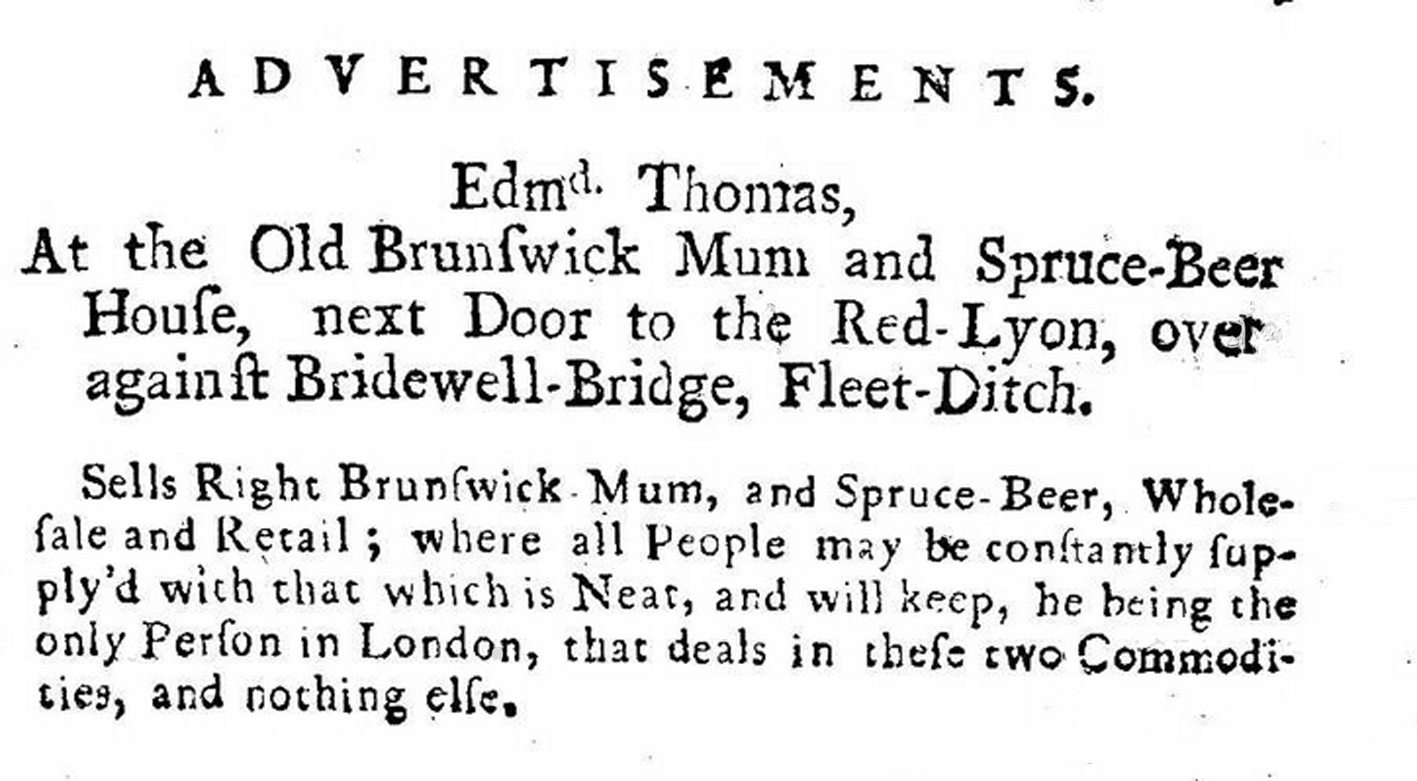

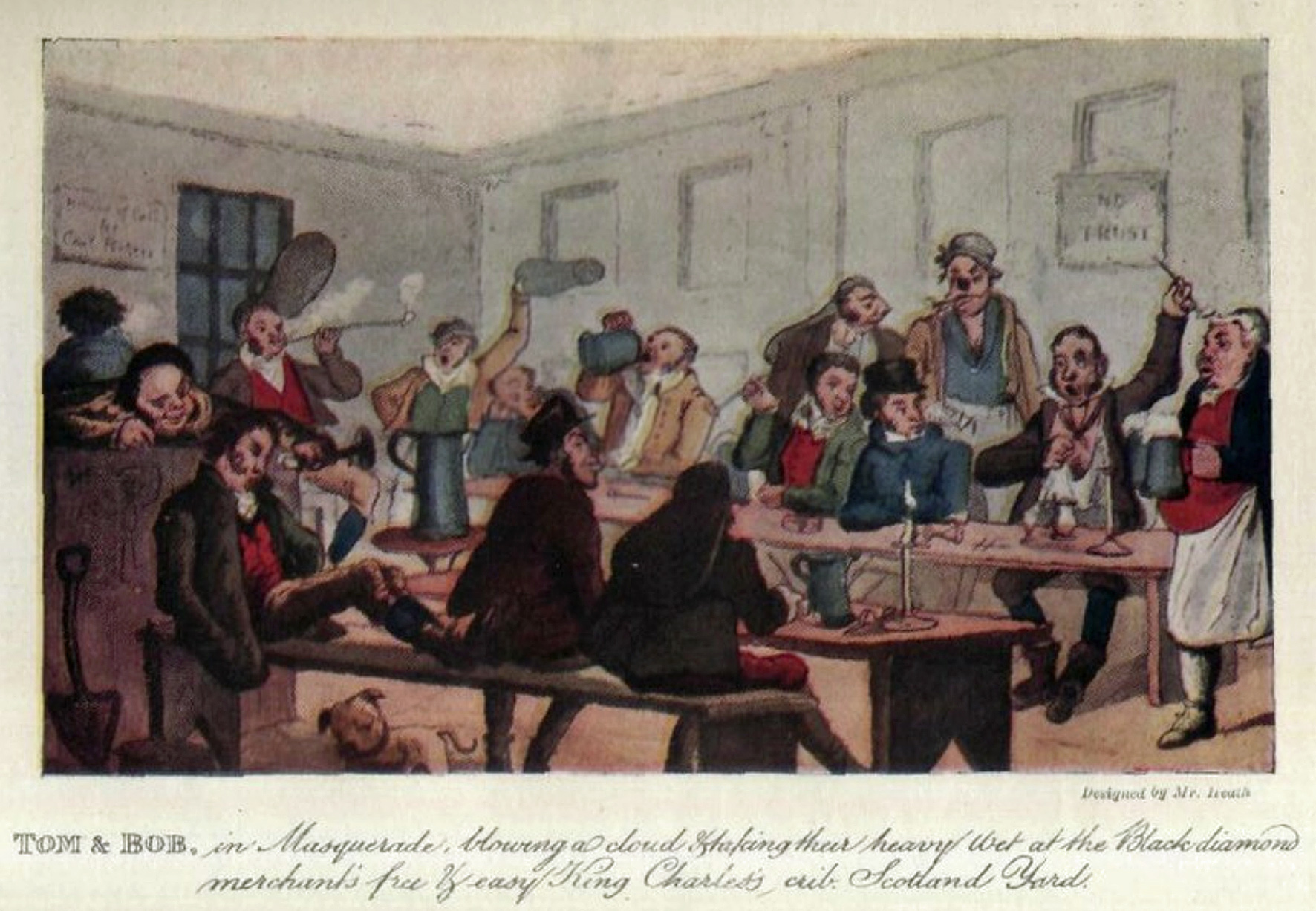

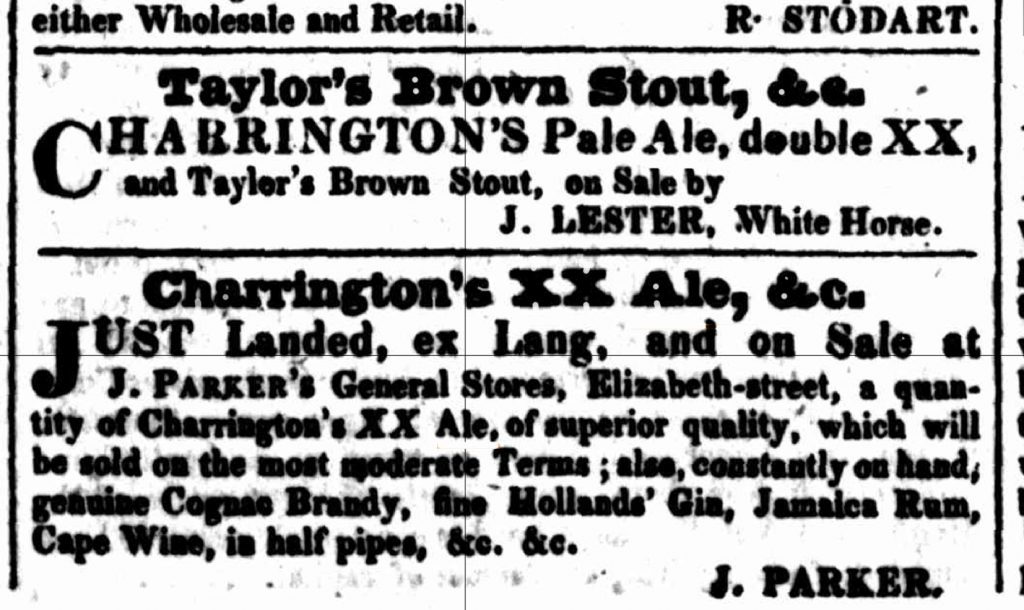

Though it was “disagreeable to the taste of many”, spruce beer was a popular drink in Georgian Britain, with The Family Receipt Book declaring that “notwithstanding its invincible terebinthine flavour,” it “forms so refreshing and lively a summer drink, that it begins to be greatly used in this country.” Local newspapers carried advertisements for the imported spruce essence needed to make it, and for local retailers who sold it. J. Lambe, “Purveyor to his Majesty, at his Warehouse, New Bond-street” in London was advertising that he made and sold “the best double American Spruce Beer, which on trial by those who have been in America, will be found of a finer flavour than can be made there from the fresh branches.”

An advert in the Hampshire Chronicle of 5 May 1790 for “essence of Canadian spruce” sold in pots for two shillings and sixpence a time “with directions for making it into Beer” listed more than 20 retailers around the county where it could be brought, including Skelton and Macklin in Southampton, while the City Coffee House, Bath, for example, was advertising in July 1800, a few months before the Austen family moved there, that it sold “Bottled Cyder, Beer, Porter and Spruce Beer”.

The Family Receipt Book gave instructions on how to make spruce beer at home that must have been very close to the method the Austen household used:

“The regular method of brewing spruce Beer, as it is at present in the best manner prepared, and so highly admired for its excessive briskness, is as follows: Pour eight gallons of cold water into a barrel; and then, boiling eight gallons more, put that in also; to this add twelve pounds of molasses, with about half a pound of the essence of spruce; and on its getting a little cooler, half a pint of good ale yeast. The whole being well stirred, or rolled in the barrel, must be left with the bung out for two or three days; after which the liquor may be immediately bottled, well corked up and packed in saw-dust or sand, when it will be ripe and fit for drink in a fortnight. If spruce beer be made immediately from the branches or cones, they are required to be boiled for two hours, after which the liquor is to be strained into a barrel, the molasses and yeast are to be added to the extract, and to be in all respects treated after the same manner. Spruce beer is best bottled in stone; and from its volatile nature, the whole should be immediately drank when the bottle is once opened.”

Twelve pounds of molasses was the equivalent to a bushel of malt, according to a commentator in 1725, so the Family Receipt Book’s recipe would produce 16 gallons – half an ale barrel – of beer of somewhere between 5 per cent and six per cent alcohol by volume.

There is some evidence that American-brewed spruce beer came across the Atlantic: on Thursday 17 February 1785, 158 gallons of spruce beer were auctioned off, along with other goods including tea, coffee, wine and rum, at the Custom House in Bristol, a port more likely to deal with ships from the Americas than from the Baltic. There were certainly commercial spruce beer breweries operating in the United States that could have supplied it: Medcef Eden was advertising his “double spruce beer”, “to be sold at my brewery, Golden Hill,” New York in the Independent Journal in May 1785, for example. American-brewed spruce beer was , at least occasionally, made with hops: a recipe in the New Haven Gazette from 1788 included two ounces of hops –a quarter of the amount used in a recipe for malt beer – and two quarts of bran, together with “one bundle” of spruce and four gallons of molasses to make a barrel of beer.

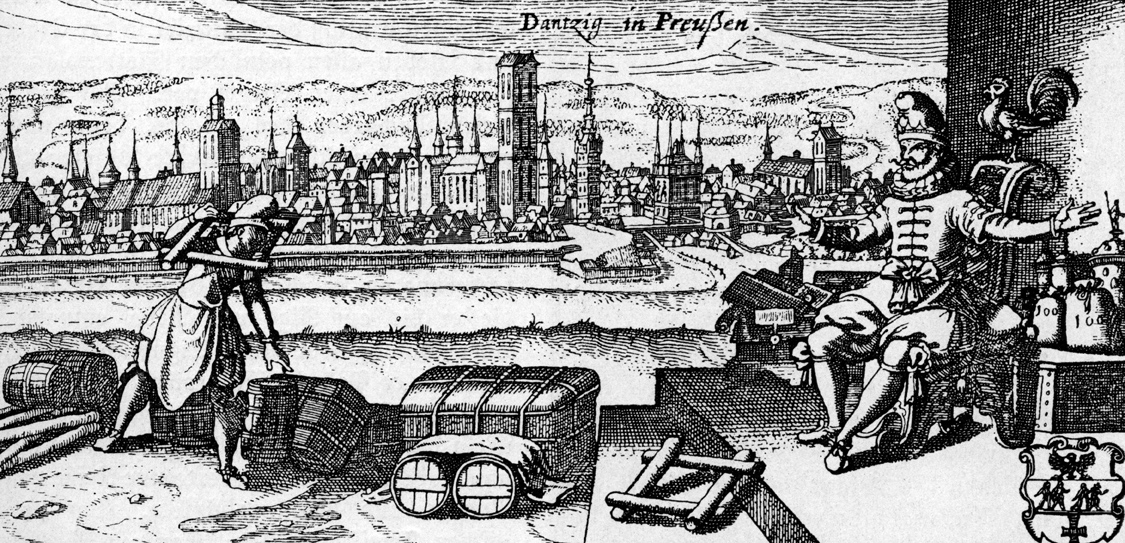

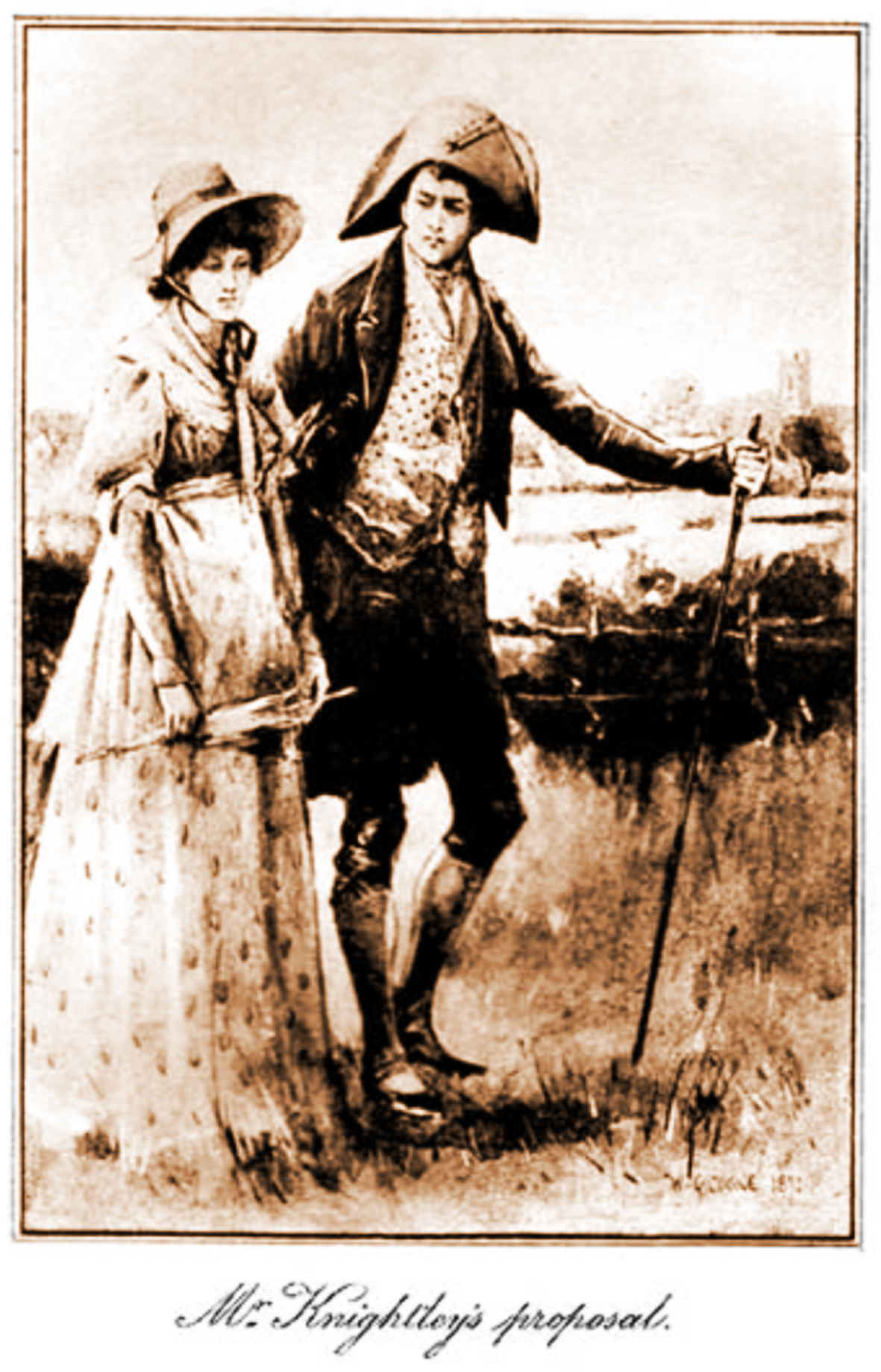

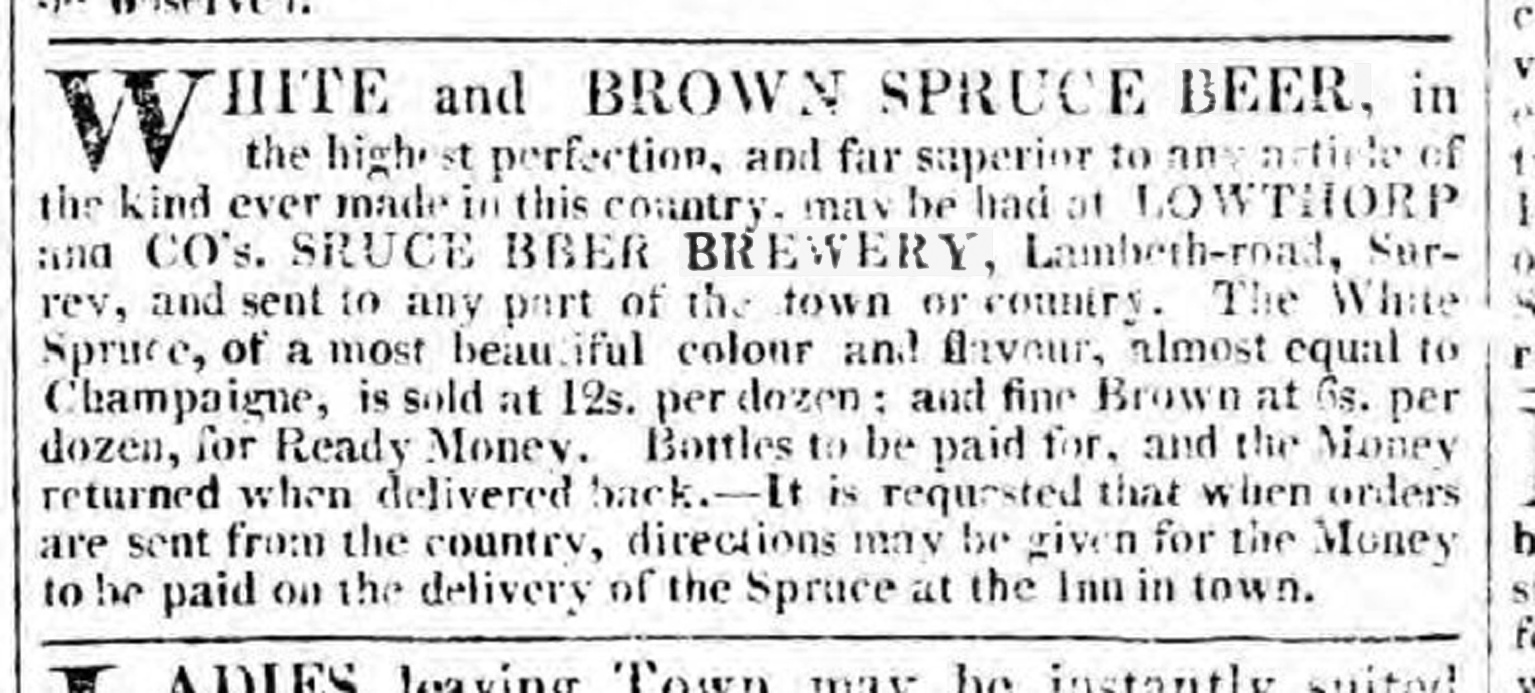

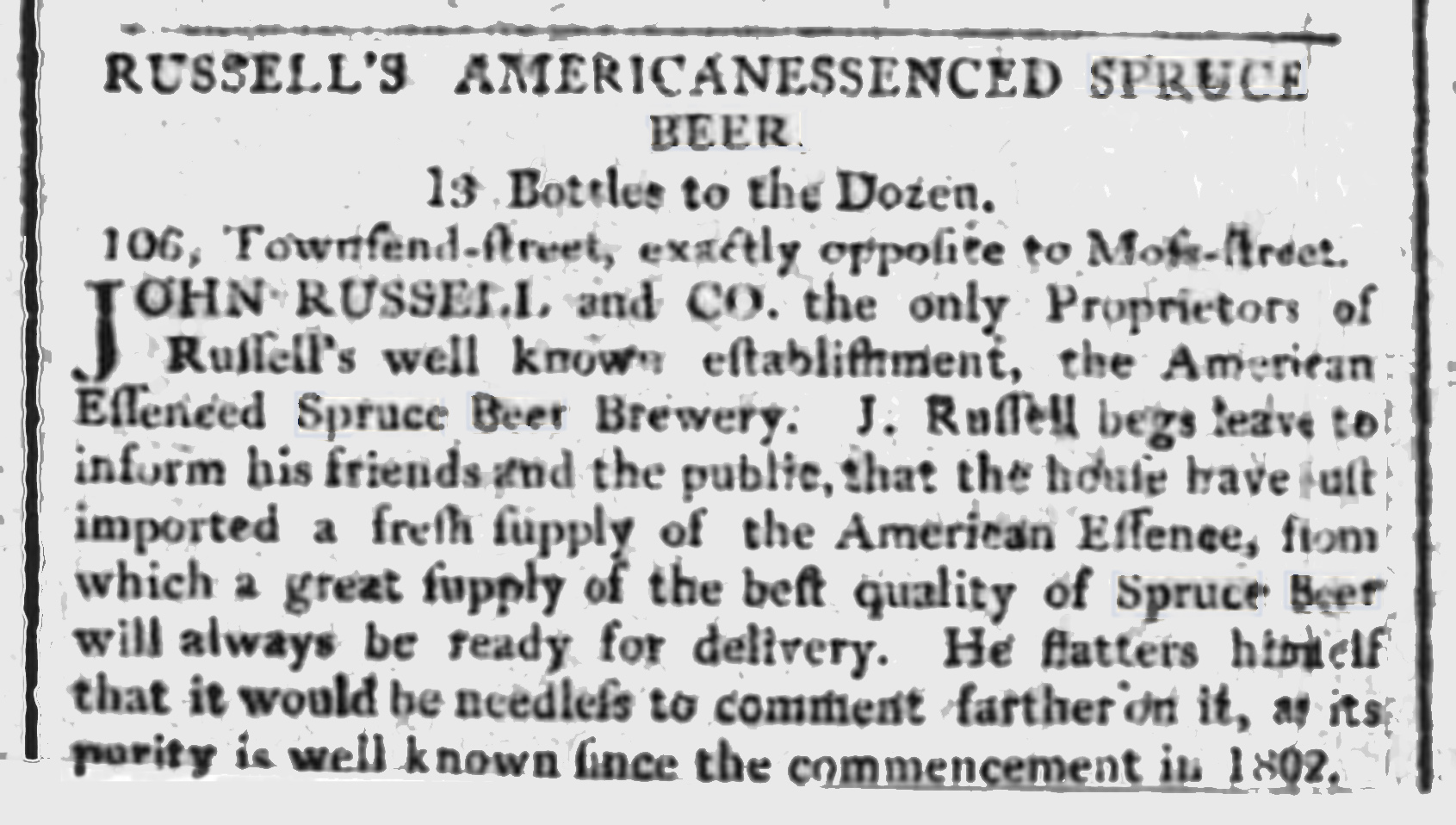

![Spruce brewery London 1806]() However, plenty of British entrepreneurs were making American-style spruce beer for those who, unlike the Austens, did not wish to make their own. The Observer newspaper on 25 August 1799 carried two separate advertisements on its front page for “genuine American spruce beer” sold by Brown’s Wine Vaults and Italian Warehouse in Paradise Row, Chelsea and “Hickson’s celebrated Spruce Beer … just becoming properly ripe for drinking”, available from William Hickson at his Oil and Italian Warehouse in the Strand. One maker in 1804 in Craven Street, just off the Strand in London, was selling “Imperial Spruce Beer”. There was another spruce beer brewery operating in London, Lowthorp & Co, in the Lambeth Road, around 1806, selling White Spruce “of a most beautiful colour and flavour, almost equal to Champaigne [sic]”, as 12 shillings a dozen bottles, and “fine Brown at 6s per dozen, for Ready Money” (white spruce beer was made with lump sugar, brown with treacle or molasses), and another in Dublin around the same time, John Russell’s American Essenced Spruce Beer Brewery, claimed to have startedb in 1802. (Spruce beer’s success was helped

However, plenty of British entrepreneurs were making American-style spruce beer for those who, unlike the Austens, did not wish to make their own. The Observer newspaper on 25 August 1799 carried two separate advertisements on its front page for “genuine American spruce beer” sold by Brown’s Wine Vaults and Italian Warehouse in Paradise Row, Chelsea and “Hickson’s celebrated Spruce Beer … just becoming properly ripe for drinking”, available from William Hickson at his Oil and Italian Warehouse in the Strand. One maker in 1804 in Craven Street, just off the Strand in London, was selling “Imperial Spruce Beer”. There was another spruce beer brewery operating in London, Lowthorp & Co, in the Lambeth Road, around 1806, selling White Spruce “of a most beautiful colour and flavour, almost equal to Champaigne [sic]”, as 12 shillings a dozen bottles, and “fine Brown at 6s per dozen, for Ready Money” (white spruce beer was made with lump sugar, brown with treacle or molasses), and another in Dublin around the same time, John Russell’s American Essenced Spruce Beer Brewery, claimed to have startedb in 1802. (Spruce beer’s success was helped ![Spruce beer brewery Dublin 1807]() by the fact that several Acts of Parliament, most notably in 1795/6, had established that no magistrates’ licence was needed to sell it.) John Munro, grocer and porter dealer, 10 South Frederick Street, Edinburgh, was advertising in 1804 “Fine Double Spruce Beer” at two shillings and six pence a dozen bottles, table spruce beer 2s, “Families who make their own Spruce, supplied with the Patent Essence and London Molasses on the most reasonable terms.” By 1806 the black spruce tree was growing in Britain, having been brought over from North America, and according to Richard Shannon, the inhabitants of Devon, Cornwall and Yorkshire were all making spruce beer from that tree and the Norwegian Spruce, which was also now being grown in the country.

by the fact that several Acts of Parliament, most notably in 1795/6, had established that no magistrates’ licence was needed to sell it.) John Munro, grocer and porter dealer, 10 South Frederick Street, Edinburgh, was advertising in 1804 “Fine Double Spruce Beer” at two shillings and six pence a dozen bottles, table spruce beer 2s, “Families who make their own Spruce, supplied with the Patent Essence and London Molasses on the most reasonable terms.” By 1806 the black spruce tree was growing in Britain, having been brought over from North America, and according to Richard Shannon, the inhabitants of Devon, Cornwall and Yorkshire were all making spruce beer from that tree and the Norwegian Spruce, which was also now being grown in the country.

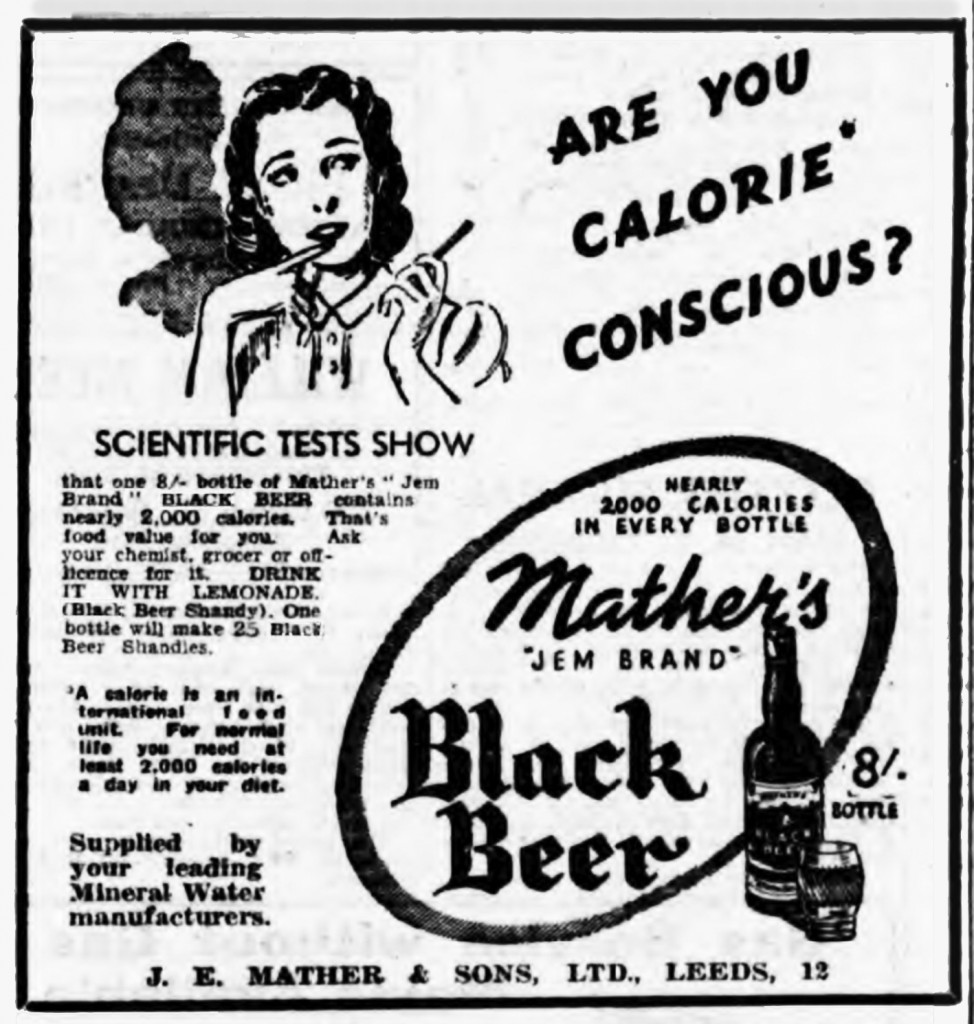

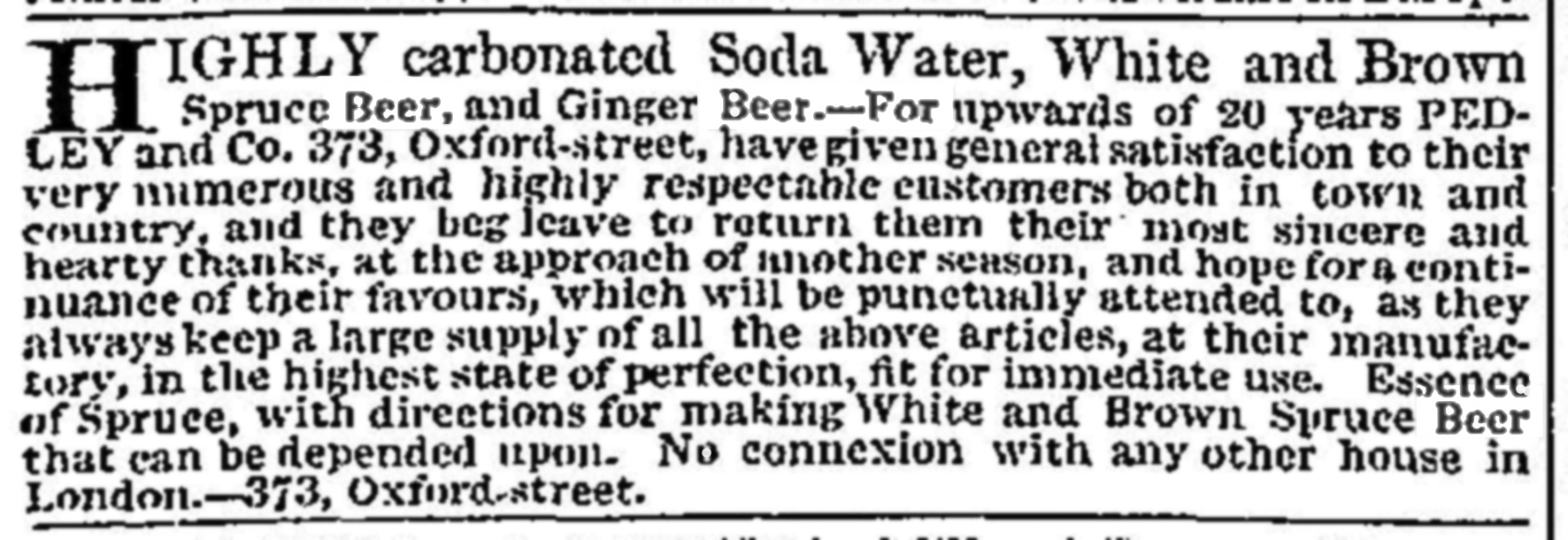

![Pedley spruce beer 1819]() In a few years, however, American-style spruce beer began to lose its popularity in Britain, perhaps because now the Royal Navy was using lime and lemon juice as its main defence against scurvy. Essence of spruce for making spruce beer was still being advertised for sale in 1819, by Pedley and Company of Oxford Street, London, who also made “highly carbonated” white and brown spruce beer themselves, as well as ginger beer and soda water. When William Parry’s second Arctic expedition left from London in 1821, each ship carried provisions for three years that included 144 bottles of essence of spruce and 1,200 pounds of molasses, but also 4,500 pounds of lemon juice in five-gallon casks (and 120 canisters of “essence of malt and hops”, each one enough to brew a barrel of brown stout, as well as 4,000 gallons of rum, eight tons of pork, five tons of potatoes, and much else). Mr Pedley died in 1821, and at the end of that year his executors put up for auction much of the equipment at his Oxford Street premises, including “two very expensive Soda Water Engines with metallic barrels, pumps etc by Bramah and Galloway, 700 dozen stone bottles, 1,500 gross of corks, 12 hundredweight essence of spruce”, and “part of a hogshead of molasses”. It looks as if Pedley may have been Britain’s last commercial essence of spruce brewer. “Viner’s Essence of Spruce, sufficient for 18 gallons of superior White Spruce Beer, price 3s 6d per bottle with proper directors” was still being advertised for sale in 1825 for do-it-yourself spruce beer brewers, but looks to have vanished off the shelves soon after. Imported essence of spruce was still being taxed at 10 per cent ad valorem in the 1840s, later changed to 2s 6d a pound: but in 1856 the tax brought in just £1, and 1867 it was declared that not one drop had been imported the previous year

In a few years, however, American-style spruce beer began to lose its popularity in Britain, perhaps because now the Royal Navy was using lime and lemon juice as its main defence against scurvy. Essence of spruce for making spruce beer was still being advertised for sale in 1819, by Pedley and Company of Oxford Street, London, who also made “highly carbonated” white and brown spruce beer themselves, as well as ginger beer and soda water. When William Parry’s second Arctic expedition left from London in 1821, each ship carried provisions for three years that included 144 bottles of essence of spruce and 1,200 pounds of molasses, but also 4,500 pounds of lemon juice in five-gallon casks (and 120 canisters of “essence of malt and hops”, each one enough to brew a barrel of brown stout, as well as 4,000 gallons of rum, eight tons of pork, five tons of potatoes, and much else). Mr Pedley died in 1821, and at the end of that year his executors put up for auction much of the equipment at his Oxford Street premises, including “two very expensive Soda Water Engines with metallic barrels, pumps etc by Bramah and Galloway, 700 dozen stone bottles, 1,500 gross of corks, 12 hundredweight essence of spruce”, and “part of a hogshead of molasses”. It looks as if Pedley may have been Britain’s last commercial essence of spruce brewer. “Viner’s Essence of Spruce, sufficient for 18 gallons of superior White Spruce Beer, price 3s 6d per bottle with proper directors” was still being advertised for sale in 1825 for do-it-yourself spruce beer brewers, but looks to have vanished off the shelves soon after. Imported essence of spruce was still being taxed at 10 per cent ad valorem in the 1840s, later changed to 2s 6d a pound: but in 1856 the tax brought in just £1, and 1867 it was declared that not one drop had been imported the previous year